A story made of fire and time

Review: Portrait of a Lady on Fire

(Dir. Céline Sciamma, 2019)

Image sourced from Pinterest

There are movies that you watch. Then there are movies that you listen to so intently, they become memory itself. Portrait of a Lady on Fire belongs to this second kind—it doesn’t unfold so much as it smolders, waiting patiently for you to lean in, to let it burn you, quietly, irrevocably.

I didn’t see it in one go. I saw it in intervals—fifteen minutes between meetings, ten before a call, twenty after a long day’s work. But even in this fragmented watching, the film never lost its hold on me. Every time I returned, it picked up as if no time had passed, its intensity preserved in the embers. Most films suffer from such disruptions. This one adapted to them—perhaps because it, too, is about longing suspended in time, about love stretched and stilled like a moment inside a painting.

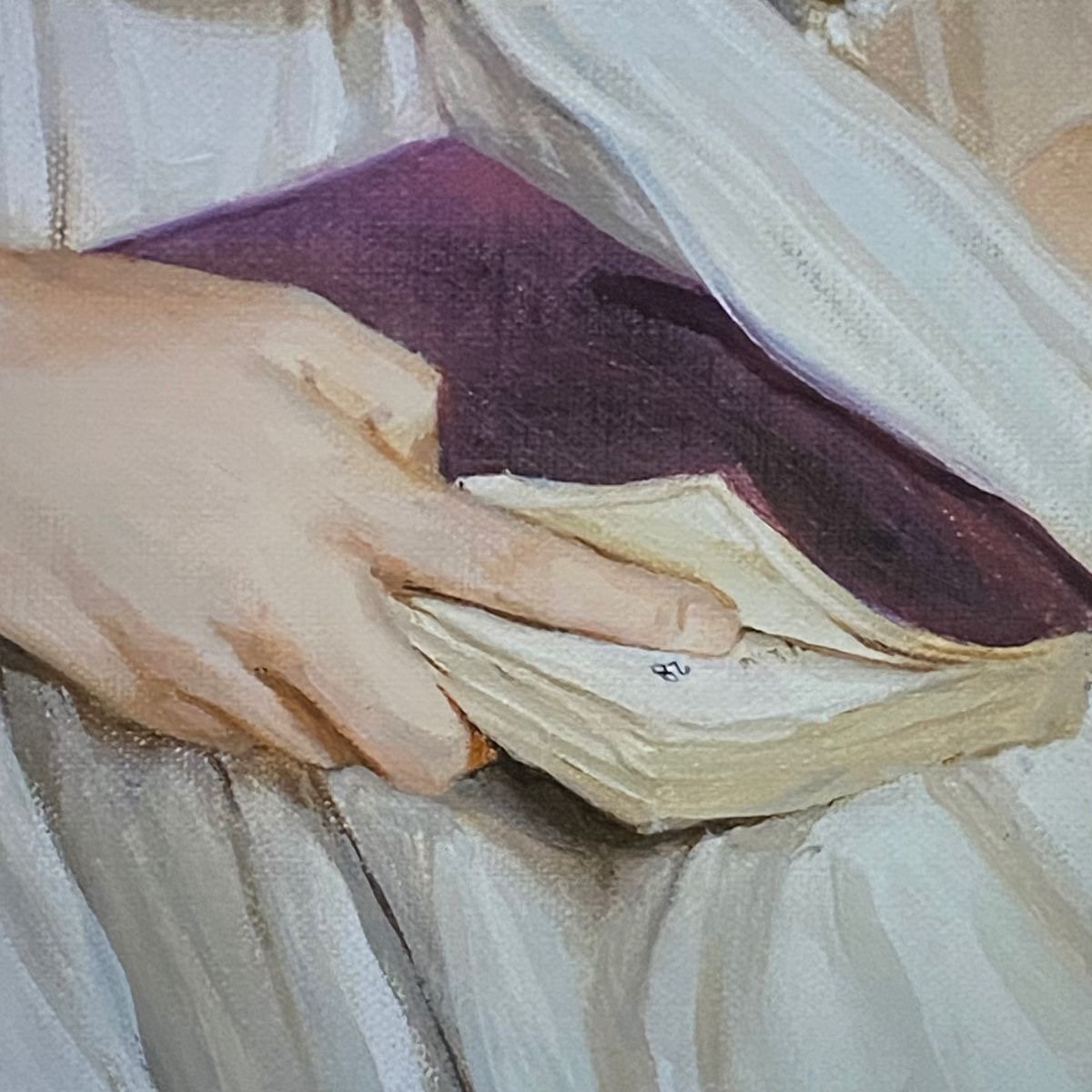

Céline Sciamma crafts the film like a living canvas. Every frame feels hand-mixed—shades of honey, salt air, and earth. There is a liquidity to the way it moves, like brushstrokes finding form. The composition is meticulous: warm candlelight bleeding into cool stone, the sea flickering like a restless conscience. Sciamma doesn’t simply create mise-en-scène; she paints with it.

The absence of a traditional score only deepens this immersion. The film chooses silence over sentimentality. The everyday becomes the orchestra—fabric swishing, footsteps echoing, waves humming against the cliffs. And most vividly, the sound of fire. It crackles through the film like a pulse—domestic, dangerous, intimate. It’s not a symbol but a presence. The fire becomes the film’s emotional metronome, marking the rhythm of restraint and release, of things that will ignite but cannot last.

The story is both simple and labyrinthine. Marianne (Noémie Merlant), a young painter in late 18th-century France, is commissioned to paint Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), who is to be married off against her will. Héloïse had refused to sit for a previous portrait, so Marianne is brought in under the guise of companionship—to walk with her, observe her, and paint her in secret. But as Marianne looks, she begins to see. And in being watched, Héloïse begins to awaken. What begins as study becomes conspiracy, becomes connection, becomes love.

Love, in this film, is an act of looking. But it’s not passive. It is active, equal, transformative. The gaze is returned. The lovers don’t just fall into each other—they rise into awareness of being seen. Their intimacy is wordless and slow, as if drawn by candlelight. Their bodies speak like poetry—measured, breathless, reverent.

The film gives them this brief paradise: a week without men, without judgment, without consequence. Sophie, the young maid (Luàna Bajrami), anchors the world with her quiet presence, her own secret rebellion unfolding alongside theirs. In this all-woman world, rituals emerge—painting, reading, abortion, music, sex. There is freedom, but also the shadow of return, of inevitability.

And then, there is myth. The Orpheus and Eurydice reference arrives not just as a story but as a prophecy. When Marianne turns back to look—when love, momentarily eternal, is interrupted by memory, by choice, by fear—we sense the fall. The lovers descend from their fiery perch into the underworld of routine, roles, and absence. But the gaze endures. Héloïse appears later, in a wedding dress, in a painting, in a memory, in music. She becomes the ghost that love leaves behind.

The film’s final act is quiet devastation. Marianne sees Héloïse again—only from a distance, in a concert hall. Vivaldi’s “Summer” floods in. The camera stays on Héloïse’s face, trembling under the weight of everything remembered. We don’t see Marianne. We only see the one who carries her.

Image sourced from Pinterest

“Do all lovers feel they are inventing something?”

Image sourced from Pinterest

Verdict:

A masterpiece of restrained passion and visual poetry, Portrait of a Lady on Fire burns with the quiet fire of recognition. A gaze held too long, a moment prolonged beyond time, a story remembered as flame. I watched it in pieces—but it has stayed with me whole.